1914 A Horse is a Horse

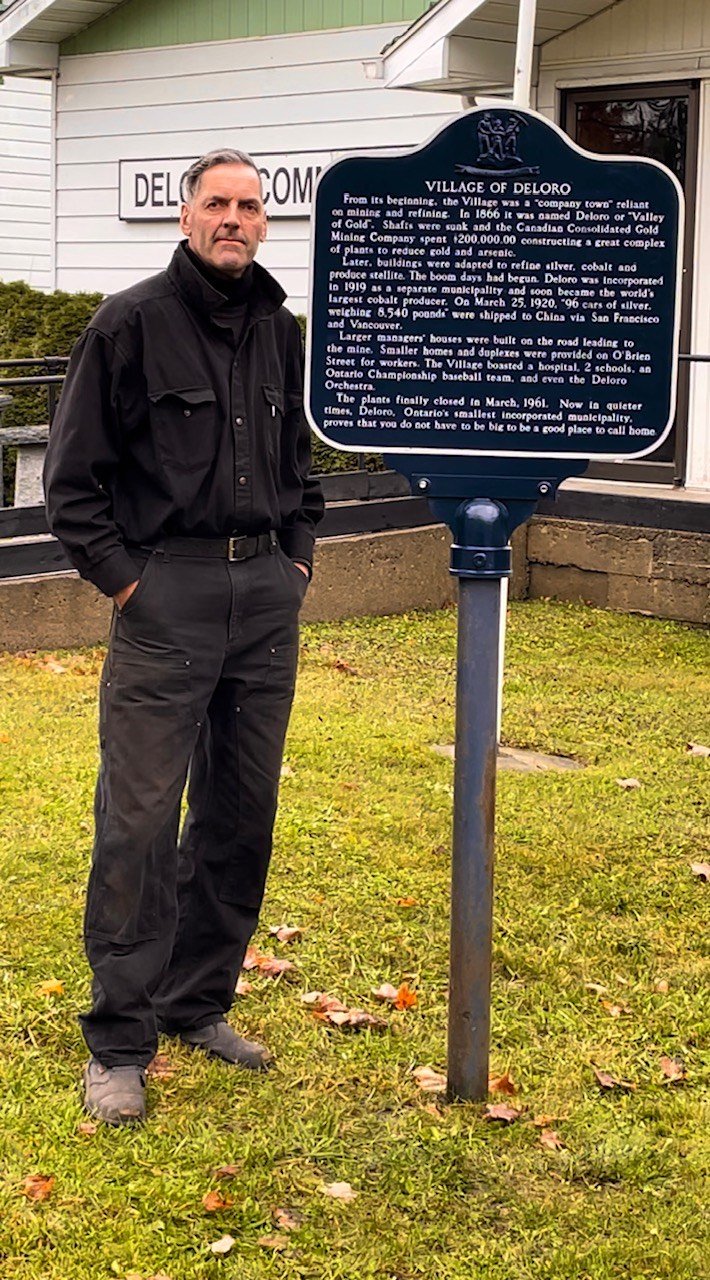

A live horse is, of course, a horse but is a horse still a horse after death? For most of us, this question may appear metaphysical but in 1914 it was enough to cause an uproar in the booming mining town of Deloro.

In those days, hundreds of industrial workers refined cobalt bearing ore at Deloro, producing thousands of ounces of silver and hundreds of pounds of arsenic a week. The arsenic was used for pesticides and, believe it or not, for body lotions, makeup and medicines.

The village was marvelously complete. With the exception of the general store, the village was owned by the Company which ran it. But the workers loved it and there wasn't that much you couldn't find right at home. The Deloro Social and Dramatic Society often put on cultural evenings featuring readings, violin solos and perhaps a few rounds of boxing.

In short, there wasn't much need to leave town, but when you did, it was generally by horse. New cars such as the Russell, which was advertised heavily in the local press, just couldn't get around on the muddy dirt roads like a horse could. When it came to dealing with horses, it was best to deal fairly, or suffer the consequences.

SLIGHTLY USED HORSE

Knowledge, they say, is opportunity and when it came to Mr. Jonas' horse, William Longmuir had two very special bits of knowledge about the wonderful white mare. First, Thomas Potts wanted to get that horse in the worst way. It seemed he would pay or trade almost anything for it. Secondly, and unknown to Potts, the horse had just died.

If this last gem of information could be kept from Mr. Potts for a little longer, Longmuir saw a very lucrative opportunity for a talented middleman, such of course, as himself.

Longmuir was able to purchase Mr. Jonas' dead 12 horse for the very reasonable price of fifty cents, owing no doubt to its new physical state. Using the recently installed telephone service, he set about finishing his plan. He called Mr. Potts with the good news that the horse was now his and available for sale.

In no time, he arranged to trade the horse for one of Potts' and (in a display of negotiating nerve) he demanded as well the sum of $2.00. Mr. Longmuir wisely insisted that the deal should be "sight unseen."

After a good deal of bickering, the deal was struck. Longmuir contrived to meet Potts on the way to his barn and picked up his end of the deal before Potts had a chance to realize that if the mare were ever to ride again, it would not be on this earth. One can only imagine Potts' surprise when on entering Longmuir's barn he saw that his much coveted mount was dead.

JUSTICE SERVED

In those days, justice came to the people. In the same hall where the Deloro Social and Dramatic Society met, Judge Burns held Sessions Court. Mr. Thomas Potts pleaded the issue of justice. Surely even if you agreed to buy a horse sight unseen, it should be alive. Longmuir pleaded the words of the bargains made. The unfortunate animal, dead or alive, was nevertheless a horse. A horse was a horse and a deal was a deal.

As perhaps befits one who chose so legalistic an approach, Longmuir hired a lawyer. His Honour reserved his decision.

This case was not, however, to be the last that the court would hear of Jonas' horse. Mr. Jonas wondered why it died in the first place. Although the judge could have been forgiven for fearing the litigants were flogging a dead horse, Jonas proceeded with a suit against George Emigh. Emigh, it seems, had borrowed the horse for a ride to Cordova. Because Emigh had not cared for it properly, said Mr. Jonas, it died.

Now, then as now, only a judge can decide what the law is. Therefore, only a judge could decide whether a dead horse was a horse nonetheless. But this second case against Emigh involved a question of fact- why had the mare died and was it Emigh's fault? Then as now, juries seemed the best way to determine facts. A jury was promptly formed of "reliable men" or so the newspapers said.

In our times we are used to juries who are impartial. If you have even read about the case, you may be excluded. Not so in 1914, at least not so in Deloro in 1914. This jury of "reliable men" included one whose reputation was described by the newspapers as being 100 degrees in the shade. The foreman was none other than that old dead horse trader himself, William Longmuir.

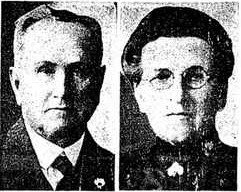

Thomas Potts not only ran the Deloro Boarding House, but also the Royal Hotel in Marmora, and the Tipperary Hotel on Crowe Lake.

Longmuir returned from deliberations with his jury and walked to the centre of the court. He read as follows: "The jury finds the value of the horse to be forty dollars. And the jury, after viewing all the evidence in the case, believes the horse, the property of Mr. R. Hook Jonas, came to its death from pneumonia, contracted from a cold due to heavy drinking, being given the said horse by Geo. Emigh and the said Jury recommends that Mr. Jonas has lawful grounds for proceeding against Mr. Emigh for collection of the said sum of $40. Said sum to be paid in court.

It now appeared that Mr. Longmuir had, as juror, penalized Emigh for killing by negligence the same horse, that he as litigant argued was still an appropriate item of barter. As may have been predictable, this ability to see things his own way did not impress the citizens of Deloro. A great deal of argument buzzed through the court at this, and scraps were the thing of the day.

Although he seemed to have lost his case and to have had to return the horse he traded from Mr. Potts, Longmuir doesn't appear to have had let a little thing like Deloro Sessions Court stop him. A brief postscript in the Herald reads: Potts' horse is missing and Longrnuir having said that he intended to take the horse as his property, is in danger of arrest for horse stealing.

Andre Philpot

Potts Thomas Ephrain, 1872-1952, hotel keeper oldest L.O.L. member