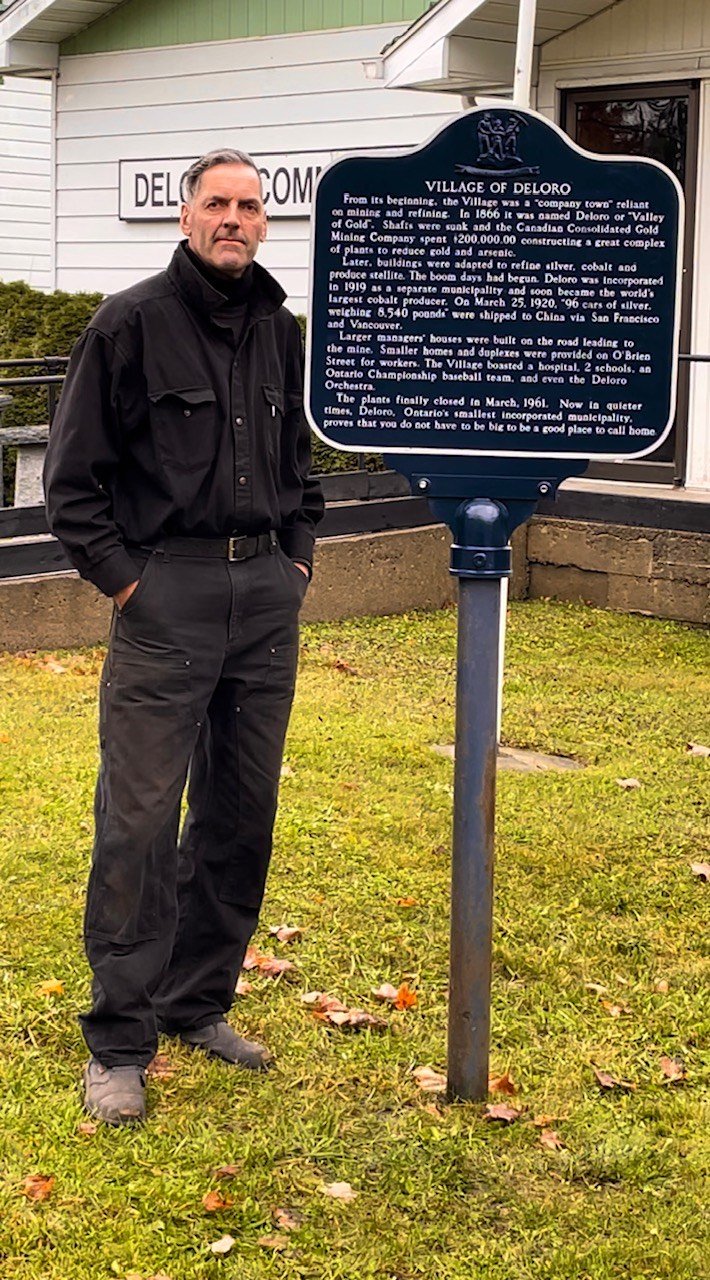

Montreal's McGill station celebrating montreal's first two mayors in stained glass

PETER McGILL AND THE BANK OF MONTREAL'S BAD DEBT

McGill Street in Marmora, believe it or not, was named after a man born as Peter McCutcheon. (August 1789 – September 28, 1860) As Peter McCutcheon, he arrived in Montreal from Scotland in 1809 and became a furrier's assistant. Montreal was the premier commercial city of Canada. It was a place of opportunity and McCutcheon was not one to miss an opportunity. Over the next ten years he realized that the key to the growth of the country would be transportation and manufacturing, not just the sale of furs. When he later became known as Peter McGill, he would invest in canals, steamships & railways, and he would lose a large sum of money in the Marmora Ironworks started by Charles Hayes.

But first things first. How could a Mr. McCutcheon become a Mr. McGill? In the early 1820's, he made a pledge which would change not just his name, but his fortunes. McCutcheon had an uncle, John McGill in York, whose wish for an heir was never granted. By 1821, John McGill had amassed a substantial fortune, largely by reason of the patronage he had received from his friend and former military commander, John Groves Simcoe. When Simcoe became Lieutenant Governor, he did not forget his friends.

John McGill was now a widower and he had no children. His fortune would go to his nephew, Peter, but only on the condition that Peter McCutcheon formally changed his surname to McGill. By Royal Charter, Peter McCutcheon become Peter McGill on March 29, 1821. He thereby secured an inheritance which would establish him as a major financial power through Canada.

Bank of Montreal's first branch

In 1819 Peter McGill became a founding director of Canada's first Bank, the Bank of Montreal. He would later be its long term president. McGill made some extraordinarily wise investments - and one extraordinarily bad one - in the Marmora Ironworks. The Ironworks were built at the first mine in Upper Canada. They were to be, by far, the largest industry in the Province. Surely, thought McGill, a chance to invest in them was an opportunity too good to ignore.

McGill seems to have been involved in the Ironworks from the very start. At first as a financier for Charles Hayes, and later as the owner by default, McGill would find that there was no money to be made at Marmora. Although he would fail here, he seems to have been succeeding everywhere else.

AN INTERESTING BIT OF CANADIAN RAILWAY HISTORY

Artist J.D. Kelly's painting of first railway

The first Canadian set of tracks was a ramshackle affair with wooden rails joined by iron splice plates, but crowds came out to watch its locomotive's inaugural run. This was the Champlain and St. Lawrence Railroad which opened on July 21, 1836, covering 14 miles from La Prairie, south of Montreal, to St. Jean sur Richelieu. Backed by John Molson, the Montreal brewer, its little locomotive, the Dorchester, had been built in Newcastle, England....ran at an average speed of 14 miles per hour .

Excerpt from Intro of"The Golden Age of Canadian Railways".

(The engine was used until a boiler explosion and derailment in 1864 near St. Thomas, Quebec, caused extensive damage.)

There were, in fact, few projects in the country in which he was not involved. He was the founder of the St. Andrews Society in Montreal. He was the second mayor of Montreal, but the first English speaking mayor. He was the Speaker of the combined Legislatures of Upper and Lower Canada. In 1836, he was the president of the company which established the first train service in Canada, St. Lawrence & Champlain Railway. On opening day his little "Dorchester" railway engine ran 14 miles on wooden rails towing four cars. Behind it a team of horses trudged dragging the other 12 cars too heavy for the engine. It was, nonetheless, proclaimed a great success.

McGill was at the peak of Canada's business, social and political power. But from Marmora he never could extract any profit. The mineral supply was wonderful; Hayes' blast furnaces were marvelous; his village established, but it was all in the middle of nowhere. You just could not make money dragging ton after ton of iron, thirty-five miles down hopeless roads to Belleville.

Peter McGill

McGill soon wanted to sell his stake in Marmora, but there would never be a serious buyer. For 40 years he was stuck with what we would now call a "white elephant". Even at his death in 1860, he still held a large interest. Shortly after his death, his wife sold some lakefront property on Crowe Lake to members of McGill's natural family - the McCutcheons. By this time they would use it for cottage lots. Tourism was already a much better business than iron mongering.

Click here for the Dictionary of Canadian Biography